We use cookies to ensure you get the best experience on our website. Learn more about our privacy policy.

Attention

This is an external link. Click “OK” to continue.

This diagram lays out the key safety dimensions of existing NSAIDs, and their positioning according to the two main safety requirements. As it is meant to describe a typical clinical situation, it is necessarily approximate.

Used by 30 million Americans each day, NSAIDs are a unique category in their ability to reduce both pain and inflammation. With their non-addictive nature and well-established efficacy, NSAIDs have become a drug class of choice for many forms of pain and inflammation. However, they are widely known to cause gastrointestinal damage in normal use, a high-priority safety issue that has not been solved. Moreover, all NSAIDs both cause and then retard the healing of existing gastrointestinal ulcers. Notably, NSAIDs are also the leading cause of drug-related deaths in hospitals, primarily from gastrointestinal bleeding.

While acting as an anti-inflammatory in the body as a whole, NSAIDs (and other common drugs) can inflame and damage the gastrointestinal tract, leading to ulcers and bleeding in 20-25% of the population. This damage mainly arises because NSAIDs suppress prostaglandin production and block blood-clotting, impairing the body’s ability to maintain the mucosal layer that ordinarily protects the lining of the digestive organs.

Because NSAIDs are uniquely effective, several approaches have been attempted to protect the gastrointestinal tract while maintaining efficacy and not compromising safety:

While traditional NSAIDs block both COX-1 and COX-2 enzymes, the 1990s saw the introduction of NSAIDs that specifically inhibited COX-2, based on the premise that NSAID-related stomach damage was primarily due to the effects of reduced COX-1. While these drugs were dramatically successful commercially, the FDA eventually removed several from the market, due to concerns that they increased the risk of cardiovascular events. Some COX-2 specific NSAIDs, principally celecoxib (branded as Celebrex), continue to be available under prescription but still pose risks to gastrointestinal health. Given today’s alternatives, COX-2 inhibitors remain the least damaging trade-off in effectiveness and safety for many physicians.

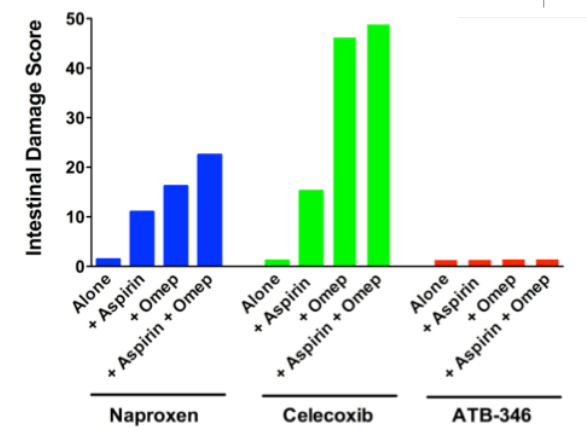

Additionally, the under-appreciated problems of using several drugs at once (“often known as “polypharmacy”, is an issue for COX-2 inhibitor users who also taking daily aspirin for secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease — even a relatively small amount of aspirin obviates the protective function served by the COX-2-specific mechanism.

Enterically-coated NSAIDs were introduced to prevent the digestion of the coated tablet in the stomach, thereby also protecting that organ from damage. However, enteric coatings are increasingly understood to be equally (or more) dangerous to patient health than uncoated NSAIDs. For example, while enteric coatings avoid stomach damage, they necessarily deliver intact pills (now absent the protective coating) into the more easily-damaged small intestine. As such, they cause more serious injury than they prevent. Secondly, enteric coatings are being shown to reduce the efficacy of the drug.

Proton pump inhibitors (e.g., esomeprazole, ranitidine; branded as Nexium and Zantac) are sometimes co-prescribed with NSAIDs to reduce stomach acidity, leading to fewer ulcers and bleeding in the stomach. However, this treatment strategy can damage in the small intestine, where reduced stomach acid leads to insufficiently digested food and survival of dangerous microbes, including C. difficile. PPIs also damage the intestinal microbiome, in addition to the non-gastrointestinal risks of osteoporosis and cardiovascular complications.

This bar chart illustrates that GI ulcers left alone will begin to heal. NSAIDs, however, in addition to their tendency to cause ulcers throughout the gastrointestinal tract, they can retard ulcer healing. In this experiment, ulcers were induced in animals that were then treated for four days. With no drug treatment (“Vehicle”), ulcers decreased in size by about 45%. Typically, NSAIDs (naproxen, celecoxib) significantly impair ulcer healing, whereas ATB-346 significantly accelerated ulcer healing.

We use cookies to ensure you get the best experience on our website. Learn more about our privacy policy.